When should I ask how many? And when should I ask how much? These expressions are very common in English, but knowing when to use them isn’t always easy. In this post I will explain the difference between many and much, and I’ll also tell you when you should use a lot and lots.

Countable and uncountable nouns

To understand the difference between much and many, first you must recognise the difference between countable and uncountable nouns.

As the name suggests, countable nouns are things you can count. They have a singular and a plural form. You can eat an apple, own four cars, visit seven countries in eleven days, and meet hundreds of people. Apples, cars, countries, days and people are all examples of countable nouns.

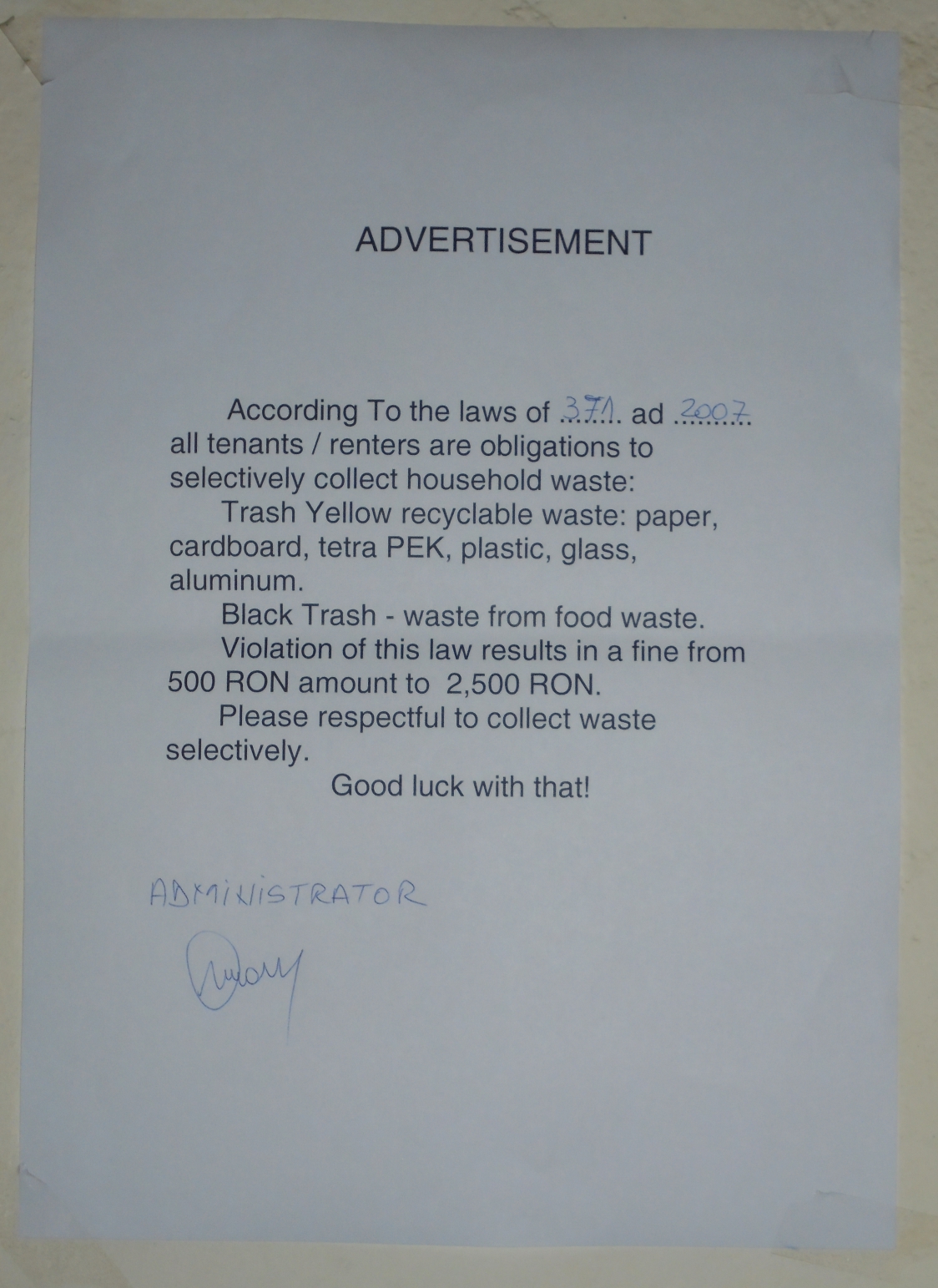

Uncountable nouns are objects or ideas that you can’t count. They don’t usually have a singular and a plural form. They can be substances, such as food, but can also be abstract ideas. A few examples are money, bread, rice, milk, sand, luck and happiness. You cannot earn *a money, drink *two milks, or buy *three breads from the bakery. You would need to say that you earned some money, drank two bottles of milk, or bought three loaves of bread.

Some other uncountable nouns:

Air

Water

Sugar

Meat

Tennis

Golf

Gold

Silver

News

Help

Knowledge

Information

Work

Magic

Traffic

WARNING:

Certain nouns are uncountable in English that might be countable in your native language, such as bread, news, information and work.

And just to complicate matters, there are also nouns that can be both countable and uncountable.

A cake (countable) is a whole cake, usually small, such as a cupcake. Cake (uncountable) usually means a piece of something much larger, like fruit cake.

Would you like a cake?

Would you like some cake?

A beer (countable) means a glass, bottle or can of beer. Beer (uncountable) is the liquid in general.

Would you like a beer?

Do you like beer?

So when do we use many and much ?

Now that you understand countable and uncountable nouns, this should be fairly easy. We use many when talking about countable nouns, and much with uncountable nouns.

Examples with many (countable):

- Do many Romanians eat fish?

- How many countries have you visited?

- There aren’t many tourists in Timișoara yet.

- There are too many people on this planet.

- There are so many flavours of ice cream that I can’t choose.

Examples with much (uncountable):

- Is there much to see in Romania?

- How much milk is left?

- There isn’t much traffic on this road.

- The government spends too much money on sport.

- I’ve spent so much time on this project but I still haven’t finished it.

Important:

Many is used with plural verb forms:

Are there many people?

Much is used with singular verb forms:

Is there much money?

Notice that all the sentences above that use many and much are either questions or negative sentences, or they use too many / too much or so many / so much. (I’ve written about too many and too much before, here.)

I often hear English learners use many in positive sentences like this:

There are many cars on this road.

This is perfectly correct English, but it sounds strange to me outside formal writing. I would very rarely say “there are many cars” or write it in an email to a friend, although I might use it in formal situations.

I also hear much used in a similar way:

There is much cake on the table.

Again, this is correct, but it sounds very strange to me, even stranger than “there are many cars”! You should avoid sentences like this outside very formal situations.

So what can we say when we don’t want to use many or much ?

Instead of saying many or much, we can use a lot or lots. What’s great about a lot and lots is that we can use them with both countable and uncountable nouns.

A lot of children in Romania speak good English.

He has lots of money.

In Romania, people eat a lot of watermelons in summer.

I played a lot of tennis at the weekend.

We’ve had lots of rain this week.

It takes a lot of confidence to speak in front of lots of people.

Note:

A lot can be used in most situations, but lots is slightly more informal.

WARNING:

A lot is two words. Even native English speakers sometimes write alot as one word, and they’re wrong! Please don’t make the same mistake!

I hope you now have a better understanding of when to use many, much, a lot and lots, and what countable and uncountable nouns are all about. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to ask me.